You are what you eat used to mean that your body is only as healthy as your diet. In today’s lifestyle economy, however, it naturally lends itself to wider interpretation. Our grocery choices reveal so much about us: our neuroses, our paygrade, they even hint at our political orientations and scientific beliefs. Our supermarkets are divided by signifiers both scientific and cultural. Low fat, gluten free, organic, fair-trade, vitamin-enriched: all responses to imbalances we perceive in ourselves and our food. With all this in mind, I was excited to come across a new kind of food label: “PROUDLY GMO.” Is this the new food craze?

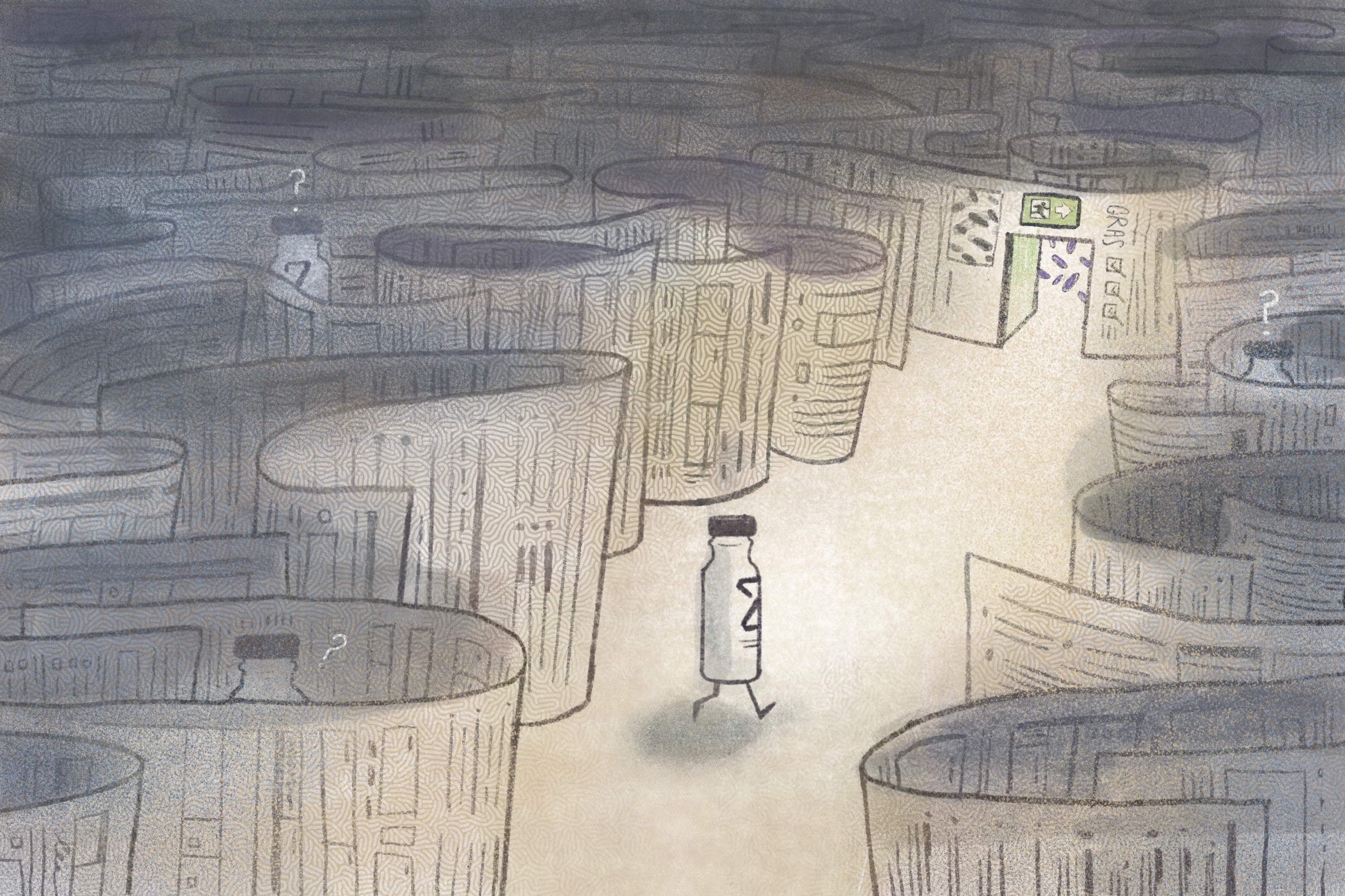

The product is interesting in its own right: a genetically engineered probiotic with a nebulous mission: preventing hangovers. Released quietly last fall by Zbiotics, a SF-based start-up whose mission statement promises “GMO for good,” it raised a lot of questions for me. As someone with a science background and a marketing job, I wondered what demographic this company was trying to reach with its “Proud GMO” designation. What cultural (or nutritional) shift was this meant to address?

As a craft beer drinker, I had more practical questions. Could the world’s first genetically engineered probiotic really help me forgo a mind-numbing hangover? Or would it just trick me into thinking that it worked? And, more broadly: how would our drinking habits evolve if we took hangovers out of the equation? There was only one way to find out.

Who’s It For?

Z-biotics is only available online, so far, and hasn’t been heavily advertised. As a result, their customer base is small enough to allow for an overview. Following a trail of internet reviews to social media profiles, you start to see a pattern. There’s Ben, the software engineer, Aaron, the bay area venture capitalist, Tania, the self-described futurist, Danielle the bio-geochemist, Jim the biohacker, and Sharon, a master’s student in biochemistry. Zbiotics has a type: young, educated early-adopters who primarily live in California and run in start-up circles. Is this the type of customer that is likely to reach for a genetically engineered probiotic hangover cure, or simply the kind of person who is most likely to hear about biotech products in their infancy? Presumably both.

The copy on the Zbiotics website (“Enzymes. Bioinformatics. Homologous recombination.”) is geared toward a science-y crowd. And this makes sense. People with high levels of scientific education tend to view GMOs more favorably than lay people. (Reasons for this include the belief that GMOs are safe for human consumption, and that organic farming is too land-intensive.) Lay people, meanwhile, are overwhelmingly disinterested in or opposed to GMOS, for a litany of interesting reasons culminating in “a general belief…in the benevolence of nature.” This divide outlines the niche, contrarian appeal of “Proudly GMO.”

Co-founder Stephen Lamb recently wrote a short essay explaining the example Zbiotics is hoping to set with its bold label. “Not labeling GMOs [has] only stoked the concern it was intended to minimize,” he argues. GMOs should thus be labelled because, as previous experiments in Vermont have shown, that actually raises consumer confidence in their safety. Zbiotics has chosen to take the lead in this by voluntarily advertising its GMO ingredients, and not merely as a way of attracting customers (“honestly, it might do the opposite,” their website says).

This divide outlines the niche, contrarian appeal of “Proudly GMO.”

Their customer-base, small as it may be, seems to be eating it up. “Got me through a bachelor party with much less pain than I deserved,” one devoted fan says on twitter. “Thank you for an extremely productive day. Far, far more productive than I expect it would have been without @ZBioticsCompany after a late night of wine(s) and business strategy!” another exclaimed. And my favorite: ”It helped me run a 10K in under an hour early in the morning after a holiday party, so there’s that :).” It’s all adorably nerdy.

How It Works

What is the nature of the beast all these people are trying to avoid? A hangover is actually a combination of different ailments. After a night of heavy drinking, we wake up exhausted, dehydrated, and nauseous, with measurable swelling in our heads. Sleeping in, drinking plenty of water, and anti-inflammatories can ameliorate some these troubles, but one symptom has proven more elusive: acetaldehyde build-up, which causes flushing of the face, hot sensations, nausea and heart palpitations.

When alcohol is broken down in our bodies, it’s first converted to acetaldehyde and then to acetate. The acetaldehyde intermediate is even more toxic than alcohol. Our livers are good at breaking it down, but not all of the alcohol you consume makes it to the liver. Some of it is metabolized by the bacteria in your gut, which never quite gets the job done. The resulting acetaldehyde buildup is the hangover bugaboo the Zbiotics team have in their sights. They found a gene that encodes an enzyme for acetaldehyde breakdown and introduced it into probiotic bacteria, and hope you’ll ingest it before pregaming.

Probiotic bacteria play important roles in our health. Some of them are permanent residents in our gut and do helpful work there, while others pass through us ingloriously. Long before we knew that bacteria could be beneficial, people swore on probiotic foods like yogurt, sauerkraut, kefir, and kimchi for their digestive wellbeing. Today, there is a gigantic commercial market that capitalizes on these beliefs. Probiotic pills and supplements promise to improve everything from our bowel movements to our brain function. And people are buying it. According to the National Institute of Health, probiotic use by adults in the United States quadrupled from 2007-2012.

There is no solid evidence that probiotic foods or supplements can actually lead to successful colonization in adults. Zbiotics doesn’t require that: you ingest their live cultures, and they churn out an enzyme that breaks down acetaldehyde for the time they reside in your gut. But does it really work?

Self-experiment

Refreshed by their truth-telling on GMOs, honored to feel deliberately targeted by a product, I decided to try Zbiotics for myself. I found the perfect opportunity when friends invited me for a weekend getaway in Blackhawk, a mining-turned-gambling town tucked away in the Colorado mountains. Blackhawk is not a high-altitude Vegas. There are no shows or dance clubs or novelty stores. The only thing to do in Blackhawk is gamble or drink — and I don’t like to gamble.

We started the evening by cheersing the tiny Alice-in-Wonderland-style bottles at a hotel bar. “Tastes like some kind of weird health tea,” my friend noted, accurately. The taste was not good, but mild, and less than a full shot. Phase 1 began with beers on the casino floor and ended with a few embarrassing photo booth shots. Phase 2 saw us down two bottles of Merlot with a small, but to-die-for lamb dinner. Phase 3 started as a quest for a casino bar with a decent DJ, led us to a few sad cocktails, and ended with a regrettably huge pile of french fries. Before going to bed, we all blew into a keychain breathalyzer. Mission accomplished: 0.1%.

Everyone experiences hangovers differently. Some people are perpetually nauseous, while other people have that rare talent of sleeping all day. Some people throw on their sunglasses and are viciously sensitive to noise. That’s not to mention the annoying few people who don’t seem to get hungover at all.

Maybe we need the threat of a hangover to keep our drinking habits in check.

When I’m hungover I am dopey. Dopey and nauseous. I have the attention span of a fruit fly, I want small bites of everything spicy or greasy, and I don’t expect relief until after I’ve gone to sleep the next night. The morning after our Zbiotics experiment, I woke up nauseous and remained that way the rest of the day — par for my very unfortunate hangover course. I did feel a bit less blunder-brained than I often do hung-over, and that proved life-saving when driving back down the snowy mountain.

On the other hand, a friend who partook with me suffered nothing but a light headache the next day. She’s convinced Zbiotics saved her Sunday, so much so that she even ordered more, and wrote about it in her fitness blog. That’s one point for Zbiotics and zero points for me. Maybe it was the French fries.

Burden of Proof

Unfortunately, neither my pity party nor glowing social media reviews count as real evidence. The Zbiotics team has gone to great lengths to demonstrate their probiotic mercenaries do as intended in a test tube. But proving that Zbiotics is effective at preventing hangovers in real live human bodies would require a clinical study, which are prohibitively expensive.

What’s more, there is no quantifiable biomarker for the presence or absence of a hangover, so such a clinical study would rely on the subjective impression of the volunteers. With no objective measure, it would be very difficult to account for the placebo effect. The hope we place in a treatment can convince us of its efficacy. For all we know, Zbiotic’s happy customers could all be benefiting from something greater than a probiotic: belief. If it works, and they do feel better, isn’t that all that matters?

Well, not quite. Maybe we need the threat of a hangover to keep our drinking habits in check. It’s practically a cultural tradition in the United States for binge-drinking college students to become polite sippers by their late-20s, when public drunkenness becomes less acceptable and hangovers become painful. Maybe we need a headache to spurn that transition. Preempting this line of inquiry, the scientists at Zbiotics are outspokenly ambivalent about bingeing. “We want to promote mindfulness about drinking behaviors,” said founder and CEO Zack Abbott in an interview.

Their product seems to cut both ways. One customer I spoke with said Zbiotics works, but, because it works, you feel like you can drink more without getting a hangover. The testimonials for Zbiotics suggest a different trend. Many users are able to recount the exact number and types of drinks they had the night before. Research has shown that if you’re counting your drinks, you tend to drink less. Perhaps this drink-counting may be a result of the product’s novelty. Will users still count their drinks the twentieth time they try Zbiotics?

The Path to Market

Regulation could have been a sticky point for Zbiotics. In the United States, approval for a genetically modified food crop takes several years, and multiple government agencies are involved. So, how is it that Zbiotics was subjected to so much less fanfare and scrutiny than genetically modified plants or animals, when they’re all created, sold, and marketed for consumption? The answer largely lays with the species of bacteria the Zbiotics team selected. Bacillus subtilis, a soil bacterium, is one of the passive bacterial passengers that frequents our digestive system, hitching a ride on produce and dust.

Because we ingest B. subtilis all the time and have for eons, the United States Food and Drug Administration has granted the bacteria a free pass known as GRAS status, meaning “generally recognized as safe.” This label, which you will probably never see adorning food labels in stores, allowed Zbiotics an easy path to market. To cover their bases, Zbiotics conducted a safety study even though they were not required for regulatory purposes. They fed a group of rats their hangover cure for 90 days, and announced in the Journal of Toxicology that it had proven entirely un-toxic.

At the end of the day, it’s important to consider the context in which people will actually be consuming Zbiotics. Every weekend or so, many of us subject ourselves to a mild form of poisoning, a cultural particularity some of us are now trying to normalize by first ingesting a soil bacterium. Maybe that detail alone will persuade some of us to reconsider our drinking habits.