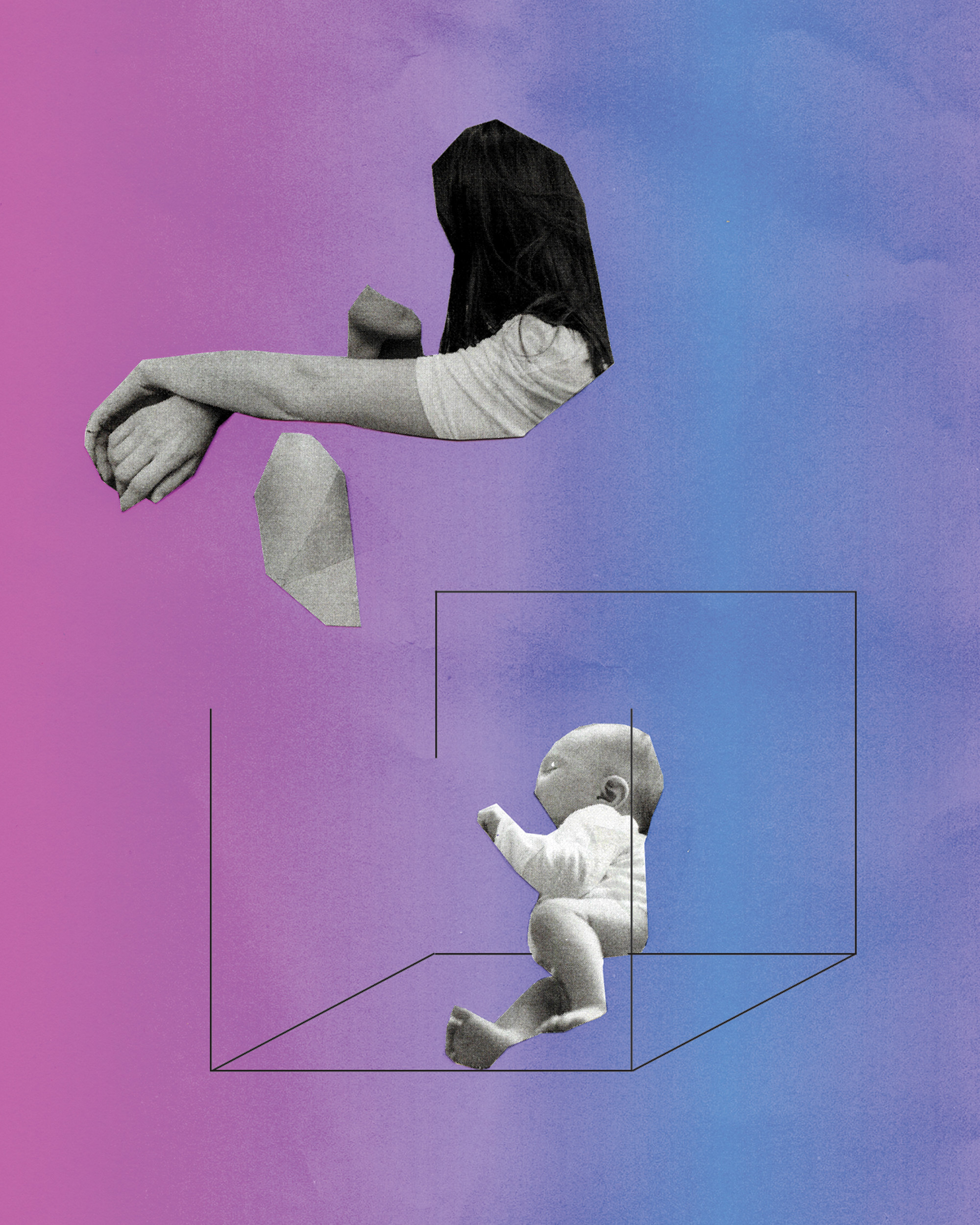

In late July 1954, New York obstetrician-gynecologist Emanuel Greenberg wrote to the U.S. Patent Office with a sketch of a fetus. His filing contained schematics for a new device, annotated to denote its constituents: a few pumps, a heater, an artificial kidney. The elements of Greenberg’s system all interfaced with a box. Within that box was his rendering of the fetus laying on its back, looking up toward the title for Greenberg’s grand idea: ARTIFICIAL UTERUS.

As an ob-gyn, Greenberg was concerned with the health of babies born too far preterm. “Only a small percentage of babies live if their weight at birth is less than two pounds,” he wrote in his patent filing, which was granted the following year. By then, technological advances in oxygenating blood and filtering waste suggested to Greenberg that those premature infants were not a lost cause.

While progress in the decades since has been slow, recent developments suggest that “artificial wombs” could one day support fetuses before viability. Technology capable of duplicating gestation without a human uterus has long captured our collective imagination. Though it’s still far off, it’s not out of reach. Human embryos have grown inside a lab dish for two weeks, and neonatal care has improved for preterm births between 21 and 24 weeks.

In 2017, researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia reported results on a system tested on preterm lambs. The group’s Biobag design — also called an “extracorporeal system for physiologic fetal support” — was able to keep lambs alive for up to four weeks of gestation. (The team makes clear in their paper that their goal is not to extend the limits of viability, which helps paint the device as “ethically unremarkable,” according to The Guardian.) A 2019 paper described doing something similar with sheep fetuses, which were delivered surgically at 95 days of gestation (the human equivalent of 24 weeks of gestation) and were kept alive outside of a uterus for 5 days.

The immediate goal of this research is to support fetal development for preterm human babies who transition to breathing air too early for their bodies to handle. It may offer hope to the families of the approximately one in ten babies born prematurely in the United States each year, and disproportionately help African American infants, since over 14% of these babies are born before they are ready.

It’s disorienting to process how close this technology is when you consider that it has long been a staple of dystopian science fiction. Picture, for example, the peachy amniotic cells in The Matrix, stacked into towers like a Japanese Metabolism-style apartment block. In this scenario, human biochemistry is harvested to run the motors of Earth’s future robot overlords while human minds are suspended in a simulation of the late 20th century. Or recall the artificial gestation units of the Borg, called maturation chambers, that were dramatized in several episodes of Star Trek. Children are suspended in these pods until they reach a level of development appropriate to begin working effectively as members of the Borg collective. Or perhaps, some fear, artificial gestation will allow for the enforcement of biological castes, as in Aldous Huxley’s 1932 novel, Brave New World.

In these dark futures, artificial wombs are organs of reproduction that enable the social control of human beings. Huxley’s vision of scientifically controlled gestation opens up fetuses to manipulation that backstops social hierarchies. In The Matrix and Star Trek universes, artificial wombs pave the way for machines or machine-human hybrids to treat humans as a kind of raw material. They benefit from the warmth, chemistry, and structure of human bodies while co-opting them for their own ends. In both cases, the technology to gestate humans outside of human bodies is imagined to be a tool of oppression and control.

This new technology may be able to expand the potential for making kin beyond the confines of the nuclear, heterosexual family.

If managed carefully, however, artificial wombs could expand the potential for creative kin-making, decouple gender and sex from reproduction, and free up women and other gestators to make more meaningful choices about their bodies. Existing birth technologies, like gestational surrogacy and in vitro fertilization (IVF), suggest that science may be able to expand the potential for making kin beyond the confines of the nuclear, heterosexual family. Technology has already enabled gay and lesbian couples to have biologically related children via IVF, for children to be born with three biological parents, and for many people with wombs—from extended family members to paid strangers—to play the vital role of gestator in a child’s life. Such creative possibilities could support ongoing feminist efforts to denaturalize the nuclear family, make parenthood available to anyone beyond the limits of penetrative heterosexual sex, and expand the circle of people involved in loving and caring for children. Sophie Lewis calls this possible future for artificial wombs the “queer gestational commune.”

Yet it is the dystopian applications of artificial wombs that have caught the attention of tech boosters. Elon Musk and his Twitter followers worry that corporations may have trouble motivating future colonists to work in his offworld ventures. Artificial wombs could solve that problem, their thinking goes, by speeding up population growth to ensure there are enough desperate people to settle Mars on the cheap. In the meantime, more profoundly, some feminists worry that artificial wombs could undermine bodily autonomy around pregnancy and abortion. If an embryo or fetus no longer needs a human body to survive, then terminating pregnancies might become even more monstrous in the eyes of anti-choice advocates. In addition, external gestation extends anxieties that artificial reproductive technologies could be coupled with new gene editing strategies like CRISPR-Cas9; that it could be used to edit out undesirable genetic traits and separate society into genetic haves and genetic have-nots. If we are not careful, artificial wombs could bring about a Brave New World-style future of further-exacerbated bio-social hierarchies.

A very fine line separates the utopic and dystopic futures that may grow out of artificial wombs. Utopian applications of new technologies are impossible when they are born into an oppressive context. Protecting against coercive reproduction by bolstering abortion rights — an increasingly unrealistic reality in America — and funding reproductive technologies for all are two steps that are necessary to make sure that artificial wombs support reproductive autonomy and social justice.

The history of reproductive innovation provides some useful reminders about how far we have come in making birthing safer, but also provides cautionary tales about how new technologies do not always make people more free and safe. In the hands of medical experts, birthing technologies have often compounded the oppression of gestators even though the goal was to improve outcomes for both them and their babies.

To prepare for a possible future of artificial wombs, and to make sure that future turns out better than the past we wish to leave behind, we must understand this history so that we do not make the same mistakes again.

For at least the last two centuries, mostly women gestators who simply want to have a safe and relatively comfortable birth have struggled against mostly male medical experts who see rigid, rule-based procedures — an approach called “rationalization” by medical historians — as the surest path to a good birth. This transition has had tremendous social as well as health consequences, since, as historian Judith Walzer Leavitt puts it, childbirth “is a vital component in the social definition of womanhood.”

Before this change was widespread, midwives delivered most babies. As historians Richard and Dorothy Wertz describe in their sweeping history, Lying-In: A History of Childbirth in America, this was the case for most of the 19th century in the United States, whether women were urban or rural. The midwife was the woman who stayed with you through this terrifying and meaningful event. She had probably attended dozens if not hundreds of births, especially if she was an older woman, but she likely did not have structured medical training. Prayers and charms were as common as practical encouragement to the birthing person. A lot of the birthing process involved simply waiting for the body to move things along on its own.

But as the 19th century came to a close and the 20th century dawned, even country doctors more often had pharmaceutical pain relief to offer, which helped to improve their standing and grow their practices. At the same time, changes in medical training, regulations regarding who could practice medicine and attend births, and the Progressive-era fervor for building state-of-the-art medical infrastructure conspired to reduce the number of practicing midwives, increase the skills of obstetricians and family doctors, and improve the spaces available in hospitals for women.

With the shift to doctor-attended hospital birthing came a drive to rationalize the birth process, the Wertzes explain. Hospitals only had so many beds, and doctors relied on a high throughput of patients to run a profitable practice for themselves and the facility. The time pressures meant that the old midwifery approach of “wait and see” was replaced by a series of active, painful, and often dangerous interventions. Interventions followed one another in an ever expanding process. For women and doctors alike, it became preferable to block out the pain of interventions like forceps assistance and routine episiotomies with anesthetizing and memory-erasing pharmaceutical concoctions like twilight sleep. While still under after birth, countless women were also subjected to unrequested hysterectomies. Doctors, secure in their professional and cultural status as experts, used their professional judgment to sterilize women whom they personally judged to have birthed too many children or to be otherwise undesirable mothers.

What this all added up to was a significant shift in the role that women played in birthing their children. Instead of a social time spent with neighborhood women over the course of several days, Richard and Dorothy Wertz argue, birth became a sort of assembly line process limited to 24 hours or less, with the doctor in the driver’s seat. Rationalization of childbirth took the birthing person out of the birthing process, sometimes leaving them with no memory of it at all. For some, certainly, this was preferable to remembering the pain. But at many facilities, the same techniques were used whether a woman wanted to remember or not, and whether she wanted to face the pain or feel sweet, numb relief. Rationalized birth in the middle of the 20th century was too often birth without choice.

More recent technological innovations in birthing have placed more emphasis on granting agency to birthing people and their families. In response to the loss of autonomy that women experienced in the first half of the 20th century, midwifery, lactation, and feminist activists restored some aspects of women’s ability to make choices about their procedure. The first stirrings of activism started early in the post-war period with the founding of organizations like La Leche League and the establishment of some of the first hospital-based midwifery practices. By the 1970s, there was a clear, national movement to return control over birthing bodies to the birthing people themselves in the United States. Consent was now routine, for example, before sterilizing women immediately after childbirth — though brutal and unjust exceptions continued to be made for Indigenous, Black, disabled, and incarcerated women, some of whom have been subject to forced sterilizations even into the 21st century.

The groundwork for women’s autonomy in pregnancy and childbirth was largely in place when assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) like in vitro fertilization became an option for families who could afford it in the 1990s and 2000s. These technologies offer more than just agency; they also offer opportunities for creative kin-making. Anthropologist Charis Thompson argues that using ARTs to make babies also creates parents in a process she calls “ontological choreography.” When all the pieces work — when preimplantation and prenatal testing shows “normal” results, when all genetic parents and gamete donors (and surrogates, if involved) sign off on the legal paperwork agreeing on who will count as “parents” when the baby is born, when doctors are attentive to parents’ needs and warning signs of medical issues, and so on — parents are made as well as babies.

While legal structures governing birth and adoption already afforded some ability for a child to lack a genetic connection to their legal parents, reproductive science has further expanded who can become a parent and how biologically related or unrelated children are to their parents. Same sex parents, single parents, and parents who can’t conceive through sexual intercourse can birth babies using gamete donation or have their babies gestated by surrogate. Depending on the technique, babies can have varying degrees of biological relatedness or non-relatedness to the legal parents, by choice and by preference. Babies can even have three biological parents, if genetic material from two parents and an egg cell from a third are carefully combined. One parent can birth one, two, three, or even eight babies at the end of a single pregnancy.

Modern, technology-assisted birthing is thus a deeply creative process, even as it is highly rationalized to fit into medical and technological standards. As feminist scholars Donna Haraway and Adele Clarke point out in the introduction to Making Kin not Population, we live in an age where both technological and societal imperatives have decoupled making kin from making babies. Modern reproductive technologies allow people to do both at once with great flexibility and creativity about who counts as kin.

It is, as Kim TallBear contends in the essay “Making Love and Relations Beyond Settler Sex and Family,” merely the ideology of white, settler patriarchy that makes us think kin-making must follow rigid rules, rules which are themselves exclusionary and destructive. TallBear contends, “white bodies and white families in spaces of safety have been propagated in intimate co-constitution with the culling of black, red, and brown bodies and the wastelanding of their spaces. Who gets to have babies, and who does not? Whose babies get to live? Whose do not? Whose relatives, including other-than-humans, will thrive and whose will be laid to waste?”

While artificial wombs could lead to creative forms of kinship, societal attitudes and regulations governing bodily agency, reproductive choice, medical rationalization, and other forms of expert control will need to be proactively managed. If artificial wombs are introduced into our current culture willy-nilly, dystopian scenarios are all but assured. For example, if fetuses can survive outside a gestator’s body, how might that affect the moral status of abortion? This next step in the rationalization of birth might pose threats to the autonomy of the people birthed via artificial wombs as well. Some in the tech world already imagine a future in which artificial wombs will be used to quickly produce a surplus labor force to work on future megaprojects. But what of the rights of those children to choose their own fate?

With the overturning of Roe v. Wade, it is not farfetched to expect that parents could be forced to watch their fetus develop via compulsory external gestation when they simply wished to terminate a pregnancy. The political winds are trending toward compulsory gestation even without novel technologies available to help the process along. And under the current privatized healthcare system in the U.S., if a fetus was gestated against parental wishes, who is on the hook financially? The parent or parents might still get billed for months of laboratory and NICU costs that could balloon into the millions. Parents would start parenthood burdened by crushing debt to care for children they did not want in the first place, and technology could enable this lack of self-determination. Or, perhaps, they could give them up for adoption and still be on the hook, most likely, for the costs of gestational care. They would lose both a living child they were not prepared to bring into the world and any chance of financial stability for years, if not decades, to come.

A second dystopian future for artificial wombs is the baby factory scenario, in which the rights of children birthed through artificial gestation are considered less important than those birthed naturally. This is almost an inverse of the world sketched out in the 1997 movie Gattaca, where genetically engineered children are designed to have reduced incidence of a wide array of diseases. These individuals have both a biological and cultural edge, as parents of traditionally-conceived children seem to view these children as fragile, ticking time bombs for an early death, and less than their engineered siblings.

In the workplace, genetic defects serve as basis to weed people out of certain high-prestige jobs, like serving as an astronaut. When tech tycoons salivate over the idea of a labor force that can be expanded on demand to take on hard, dangerous work, like missions to Mars, they implicitly devalue artificially gestated people relative to traditionally birthed people. Artificially birthed humans are seen as raw materials for capitalist exploitation, a faceless mass expected to have no objection — perhaps even no right to have an objection — to being shipped off away from all they hold dear on Earth to a hard existence and likely early death from radiation-induced illnesses in space. They are Marx’s lumpenproletariat on steroids. A future in which people are bred to do work that someone else assigns them to do approaches a future of human enslavement, one that United States history suggests is entirely possible.

Compulsory child-bearing and compulsory work: these are not the futures feminists want.

To truly increase the options provided by artificial wombs without introducing new harms, three things would be necessary: cheap or free healthcare and childcare, preemptory legislation and regulation placing the rights of artificially gestated people on par with biologically gestated people, and strong protections for abortion rights. Removing the potential for coercive gestation, work, and debt would go far toward weighting the possible uses of this technology toward neutral or positive ends.

What, then, is the future this feminist wants for artificial wombs?

I want a future in which artificial gestation is one of a panoply of free gestational and birthing technologies that every adult — coupled or not, rich or poor, queer or straight — can choose from.

I want healthcare to be free for all, including “natural” gestators, gestators who choose to use or must use artificial gestation, and for all children, artificially gestated or not, with all disability statuses, whether congenital or acquired.

Abortion is healthcare, so I also want abortion to be easily accessible and free.

I want a future in which new parents have at least a year of generously paid time to bond with their child, regardless of their wages, job, or working conditions prior to or following this bonding leave.

I want gestational surrogacy to remain an option for those who prefer it, but I want gestational surrogates to be recognized as workers and granted appropriate legal protections for wages and health, and I want gestational surrogacy to be free to the parents who hire the surrogate.

I have a wishlist for the institution of the family and the social support families receive. I want a future in which the primacy of the nuclear, heterosexual family is abolished. Instead, people should be allowed to co-parent children in groups with all the legal rights and responsibilities without needing a marriage certificate or the process of adoption.

I want a future in which parents — especially women, queer, and trans parents who are disproportionately targeted for abuse in our current reality — can raise their children free from fear, violence, and abuse.

I want a future in which childcare and high-quality schooling are free and abundant, in which educational workers receive skilled training and education for free, and are paid generous wages directly by the state from fairly collected tax revenue.

In short, I want a just society for children and families.

Compulsory child-bearing and compulsory work: these are not the futures feminists want.

If this wishlist seems like a utopian roadmap for society, this is no accident. Artificial wombs are a sexy technology, to be sure. But technology never operates in a vacuum. And it certainly never fixes social problems on its own. Technology is always social: it is made by people living in a society, made useful in the context of social relations, and remakes aspects of society by virtue of its use in everyday life. Usually, if there is a problem with how technology affects the important things in people’s lives, it is actually a social problem about how the technology is distributed, paid for, or controlled.

Parenthood in the contemporary U.S. is quite untenable, absent any groundbreaking technological innovations concerning who can become a parent. To make the future of artificial wombs a just one, we need to start by getting our proverbial house in order. In one version of future society, the one in which we do nothing to change how childcare, healthcare, and workers’ rights are provided and protected, artificial wombs would lead to a dark reality of compulsory work and gestation. In a different one, one in which social and financial support for health, childcare, and education are robust, artificial wombs might deliver on their promise concerning creative and intentional kin-making.

To make artificial wombs a reality, then, technologists would be best served by paying attention to the society around them. Who is suffering? Who doesn’t have enough money to feed their family three healthy meals per day or pay a babysitter while they go to work? Who cannot have children due to medical issues, but wishes they could? Who doesn’t have children because they have too much debt?

It is by providing meaningful support to the people who do not have it all, and who are not at the forefront of technology, that we can make society ready for artificial wombs.