1. The Past

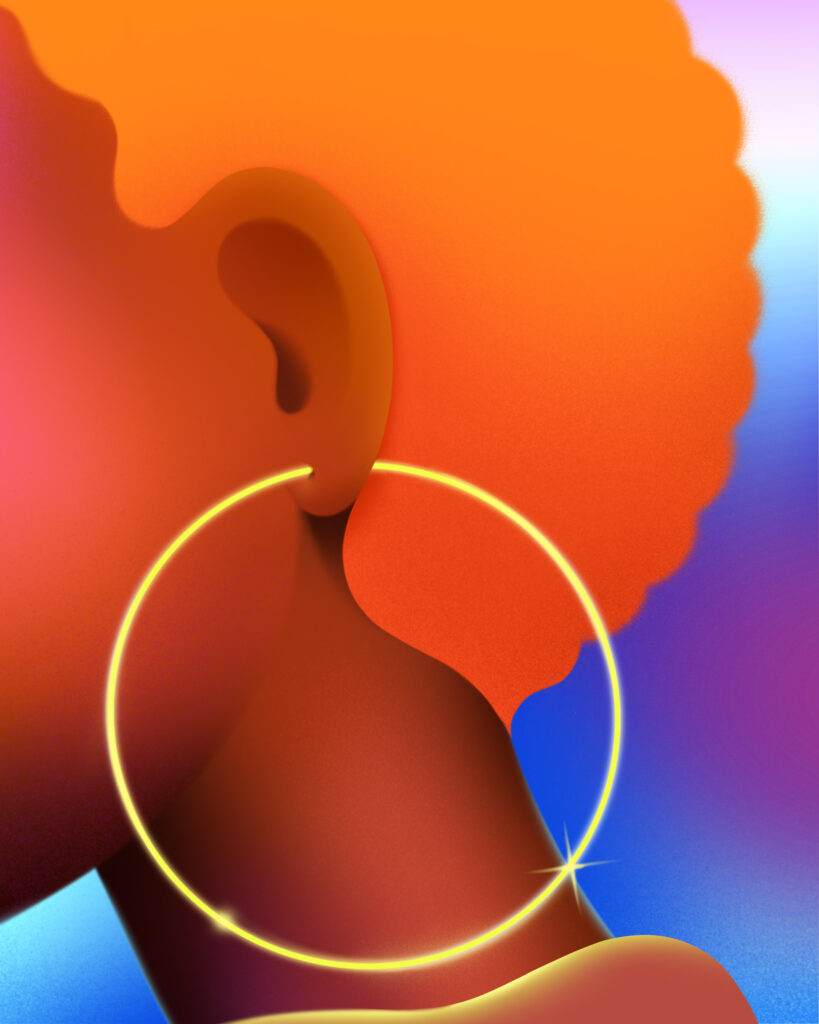

The eternal circle of gold was what first drew him to her. A golden loop, dangling large and shimmering from her left ear, beckoned him. Soon he noticed her red cowl-neck sweater, the full-blown afro he would only know later was very difficult to maintain, the tartan skirt, the light-brown skin, the curved corner of her mouth. But what had begun it all was the eternal circle of gold.

The hall was packed with hundreds of students brought together by a poster.

Do you want to build a better future? Do you want to see more tolerance in the world? We want to start a conversation. Join us! Albert Hall, Tuesday, May 24 at 2:30pm.

Such a poster could not help but attract the attention and saviorism of people in their early twenties. He was one of many, but through all those bodies, all those colors, all those languages, he still clearly made out the eternal circle of gold.

It took him some time to notice the bald head, the workman’s boots and the blue overalls made of real drill material — heavy, thick, protective — sitting next to her. They turned their head and watched him approach. As he returned their gaze, he felt that something was incomplete about them somehow. They seemed to be…searching.

He sat down right next to the red cowl-neck sweater, the full-blown afro, the tartan skirt, the light-brown skin, the curved corner of the mouth and introduced himself. Caught by surprise, she turned to face him, and, before she could think of doing otherwise, offered her name: Maggie. He looked past her and pretended not to notice the mixture of provocation and resentment in her friend’s gaze. He looked back at Maggie and, from that moment on, only had eyes for her. At least that’s how he would choose to remember it.

Over the PA system, a ‘Best Folk Revival Songs’ CD played softly while the last stragglers filed in. Odetta sang Maybe She Go, Lead Belly sang The Gallis Pole, Miriam Makeba sang Qongqothwane. Maggie’s friend sang along to all the songs…all the songs…fluently tongue-clicking along to Makeba’s Xhosa in a way that made Maggie turn back to them, impressed. Mercifully, just then, the hall’s stereo system was turned off and the voices faded to a murmur.

A lab coat handed out slips of paper. The slip he received read: “You are a devout Muslim male patient presenting with abdominal pain. Your doctor is female.” He understood; whoever had brought them here wanted them to act. He was a drama student; he would do well at this. He could certainly play a Muslim man; many people who saw him thought he was from the Middle East.

“What is this?” he heard Maggie’s friend say. From the corner of his eye, he watched them flip their slip of paper over. “Cultural exchanges,” they said. He turned his slip of paper over, and it also had the words Cultural Exchanges printed on it.

“How is this a cultural exchange?” they asked, loud enough for the lab coats to hear.

“It’s a way of enabling future doctors to have effective exchanges with diverse patients,” the nearest lab coat responded.

“Black woman. Seventeen. Unwanted pregnancy. History of abuse,” they read aloud. “You cannot make us do this. You cannot make us act out stereotypes.”

“We are not making you do anything,” another lab coat volunteered. “It would be nice if you joined us. We need more people like you. Students from developing countries are very helpful to our doctors. They teach us to better serve patients in these global times.”

“You’ve got one thing right,” they said. “You’re perpetuating a history of abuse.”

During their protest, a disgruntled murmur rolled through the hall, several slips of paper were scrunched up, a few students headed for the door.

“We will, of course, compensate you for your participation,” a lab coat with dignified gray hair said in a soothing tone. Another lab coat with blond hair and honey in her voice named the price. It was a substantial amount for just talking to someone for an hour.

The disgruntled murmur quickly died down in the face of money.

Maggie’s friend stood up to leave. “I thought we were here to have a real conversation,” they said. Maggie placed a placating hand on their arm but did not stand up herself. They looked at her with disappointment, and then looked at him with that mixture of provocation and resentment, before marching out of the hall.

Maggie turned to look at him. He smiled at her and she smiled back. Someone always gets the girl, and he had known as soon as he saw that eternal circle of gold that it would be him. At least that’s how he would choose to remember it.

He was with Maggie when he came across the thing that would change the course of his life. He would later wish that Maggie had not been there. Unfortunately, she had been there because, like him, she kept on being asked to come back for more conversations with future doctors. Every week other students would be culled for reasons that were hard to discern, but he and Maggie survived every cut, and he was certain that they would survive all future cuts, because he was such a great actor and she was so affable.

They were triumphantly walking back, hand in hand, from one of the Cultural Exchanges when a poster screamed at them: “DO YOU WANT TO LIVE FOREVER?” In that moment, with Maggie by his side, he had definitely wanted to live forever. After he tore off the first small rectangular strip of paper that had had to squeeze so much information on its tiny surface area: Live Forever Clinical Trials. Call 1-800-AGELESS — he was happy to see Maggie tear one off too. He liked that she also felt the warmth of their togetherness, but, more than that, he liked how she had, in the short space of their knowing each other, started to follow his lead.

They suddenly appeared before him and Maggie, hands in the pockets of their overalls. The mixture of provocation and resentment swept over him but by the time their gaze landed on Maggie’s face it had transformed into a much softer look of deep hurt.

“Have you seen these posters anywhere else on campus?” they asked. He could not say that he had, and neither could Maggie. “And yet here, in the place where they have enticed us to do their so-called Cultural Exchanges with money they know most of us will never walk away from, as students from ‘developing countries,’ you cannot take five steps without being asked if you want to live forever.”

He knew they had been warning Maggie about this place the whole time. Now he had finally understood what they were searching for. The shaved head, the workman’s boots, the blue overalls were all part of their search for a politics that could easily fit. He felt sorry for them, never considering that he too should have been searching for such a politics.

During the first day of clinical trials, the lab coat with dignified gray hair and the lab coat with blond hair and a honeyed voice told them all about cells and the things you could do to them: reprogramming skin cells, refreshing older cells, rejuvenating old cells, flushing senescent cells out altogether. They learned that every cell contains lived experience; that this build-up could be flushed out too, rejuvenated, a blank slate ready for a new experience. It was the lab coat with the dignified gray hair that mentioned the price this time: more money than he had known what to do with at that stage of his life. The honeyed voice told the subjects that it was the least the lab coats could do given their invaluable contribution to the field of science. When the honeyed voice spoke of telomeres and teratomas, he appreciated the alliteration.

He and Maggie, along with a group of students from “developing countries,” walked past the bald head, the workman’s boots and the blue overalls every last Friday of the month, on their way to the clinical trials. They had become a one-person silent protest called B.A.R.E., which sounded very enticing until you realized that it stood for Blacks Against Racial Erasure. They made their own placards, which were cryptic at best: “Remember Tuskegee,” “Educate Yourself About Henrietta Lacks,” “Does The Name John Quier Mean Anything To You?” “Do Not Be The Saartjie Baartman To Albert Hall’s Georges Cuvier.”

Since they never said anything, just raised their fist, bowed their head and held up their placard, they were easy to ignore. Most of the students walked past them with their heads bowed as well. He also followed suit even though he was not sure why. Maggie was different. Maggie always stopped to give them and their political cause a hug. On the day the Saartjie Baartman placard appeared, Maggie may have been crying. They may have been too. He didn’t know. He would never know. He strode on and slid back into the cold embrace of Albert Hall.

Certain things are not supposed to work. Things you find at the back of magazines, things you see advertised on television at 3 a.m., things you tear off in small rectangular strips — these things are not supposed to work.

2. The Present

He can’t get the tone right. Thirteen takes yesterday and still…The line is simple enough: “I love you, Cosette. Please remember.” The action is simple enough: he needs to gently take the waif-thin, white-as-a-sheet hand of his kept woman and give it a tender squeeze. That part he does perfectly. It’s his vocal inflection that leads to the “Cut!” every time. Why can’t he get it right? Perhaps he should try switching the lines: “Please remember. I love you, Cosette.” Yes, that has a better rhythm. It’s something he can roll off his tongue with more conviction. He feels better. Relaxes.

He’s in his trailer, a makeup artist applying the right amount of shading to his jawline to give it the definition that his fans have come to love, when he receives a call from Unknown. He looks at the screen for a beat…He has never received a call from Unknown on this number…Two beats… He has another number that is handled by his PA for that…Three beats…This must be a known Unknown. He picks up.

Without verifying that it’s him, Unknown says, “Something has happened to Maggie.” He recognizes the voice immediately. The last time he heard it, it was saying, “The problem with color-blind casting is that it has the potential to erase real histories and lived experiences. I am all for creating opportunities for Black and Brown actors, but that should be in tandem with creating spaces and places for the stories of Black and Brown people to be told. It seems rather disingenuous to tell old stories in new colors.”

He wondered then if they would have said what they had said about color-blind casting if he had not accepted the role of Dorian St. Clair — or rather if the role of Dorian St. Clair had not catapulted him to fame. They are now Dr. Somebody and their thoughts on race are highly sought-after. The hand in the fisted glove now writes academic essays and opinion pieces that appear in the best journals, magazines and newspapers. He often sees them on screens wearing very elaborate Ankara head wraps. They speak in the same breath about “Mama Africa” and cultural appropriation without even a hint of irony.

“Something has happened to Maggie,” they repeat. They sound as if they are cloaked in something heavy and drapey — probably kente, mudcloth or indigo-dyed cotton.

He must have said things — made plans — because the next thing he knows he’s sitting in a private hospital room, looking at Maggie lying on a hospital bed. It shocks him to see that there is a stray strand of gray hair on her left temple. He hasn’t even begun to think of growing old.

“Cancer,” they say from where they stand looking out of the window. He tries to connect the word to the peaceful look on Maggie’s face. He cannot. “Caught just in time, they hope.”

He watches the gentle up…down, up…down, up…down movement of Maggie’s chest. He makes its rhythm his own. Breath. Life.

“You have makeup on your face,” they say as if it is the most natural place to arrive at after delivering bad news. Their back is still turned, their eyes still looking out of the window.

Who can remain so pointedly impersonal at a time like this, he wonders.

“I was on set when I received your call,” he explains.

“Dorian St. Clair,” they scoff. “Doesn’t it bother you just a bit that you play an aristocrat that owns slaves?” They finally turn to face him. There it is — that mixture of provocation and resentment. No…No, that’s not quite right, it’s a look of utter derision and disappointment. Could it be that he has always misinterpreted that look?

“Some Blacks owned slaves,” he utters the line that has been readied for such criticism.

“Blacks did many, many things,” they say, sit- ting down opposite him on the other side of the hospital bed. “And yet the most popular show for the past five years has been one in which a Black actor, playing an aristocrat, owns slaves. Do you ever wonder who it’s for?”

“It’s fiction. Entertainment.” Another ready line.

“It is representation,” they say as they gently take Maggie’s hand in theirs.

There is a silence that neither of them is eager to break.

“She loved you, you know,” they eventually say, offering a rare olive branch.

“I know. I loved — I love her too.”

“You completely exhausted her, left her almost good for nothing.” It has been a short-lived truce.

“It took me a while to find my feet.”

Even he knows that this is not the whole truth. Ten years is certainly not just “a while.” It had been difficult to find a job. He had the right ‘look’ — tall, lean, handsome, square-jawed, his features in perfect symmetry. He had the right name — it had the touch of the exotic without sounding too foreign. But he had the wrong country of origin — people struggled to pronounce its name and correctly place it on the atlases they carried in their minds. Because of this casting directors worried that audiences would have difficulty “connecting” with him. It didn’t seem to help that they thought he spoke English very well. Luckily for him, his agent believed that he had ‘it’ and stuck with him, sending him out for role after role until Dorian St. Clair came along.

“This is not the future we imagined, is it?” they say as they give Maggie’s hand a tender squeeze.

Was the future they had in mind ever the same one? He highly doubts it.

“You know, you look exactly like you did in university,” they say, really looking at him for the first time since he arrived.

He smiles at this and by some miracle they smile back. He is momentarily lost within their emotional landscape.

“There is that amazing portrait she did of you, you know the one,” they say, still smiling, and he realizes that the smile was never directed at him but at something beautiful that Maggie had created.

He knows the one. He loved that portrait not because it was of him as a young man but because Maggie had done amazing things with these symbols in the background. The symbols had been inspired by Vodun and Vodou iconography — veve, she had called them. The portrait was not of him-him but of his shadow self, which somehow seemed more like him-him than he did. It was a nod to a very famous Harlem Renaissance artist, Maggie had explained. He no longer remembers the name of the artist.

Everyone who saw that painting loved it and those who had money in their pockets wanted to buy it, but Maggie would never part with it. When someone had offered what amounted to five years’ worth of rent for it, he had tried his best to persuade her to sell it. Understanding that he would probably never land the role that would allow them to live comfortably, he had tried to reason with her, reminding her how hard it was being a waiter when you wanted to be something else. Maggie had not liked the implication that spending her days in their loft doing what she loved in order to provide for them did not come with its own particular strain.

“You could always paint another just like it,” he had said, trying to coax and convince her but ending up doing something else instead.

“What exactly is it that you think I do?” she had asked.

“You paint…brilliantly.”

It was only when she shook her head and mirthlessly chuckled that he realized that those were not the words she had wanted to hear.

“You have no idea, do you?” she had said. “Emotional work is work!”

She had picked up the portrait and turned so sharply that one of its edges had gone through a window. She had not turned around to look at the broken pieces, and instead immediately started collecting all the belongings she had accumulated in their thirteen years together. He had left the shards of glass unexamined and uncollected until the day he moved into a much cheaper, smaller apartment. The call about Dorian St. Clair came three months later.

“You look exactly like you did in university,” they repeat, but this time there’s no smile in their voice.

He looks at the stray strand of gray hair on Maggie’s left temple before his eyes meet theirs. He was right the first time: it’s a mixture of provocation and resentment but now it is clouded by something like defeat.

“What the hell happened to Maggie,” they whisper.

He is searching for the right words but can’t find them. There was a lot of talk about cells and about doing various things to them, he remembers that. There was that moment of wonderful alliteration, he remembers that. There was his absolute conviction that the liberal compensation would bring about the perfect future for him and Maggie, he remembers that. There was the use of hormones to regenerate his thymus, an organ in the immune system — if they could turn back the clock there, perhaps his aging would slow. That’s what they had done to him, but what exactly had they done to Maggie?

Certain things are not supposed to work. Things you find at the back of magazines, things you see advertised on television at 3 a.m., things you tear off in small rectangular strips — these things are not supposed to work.

3. The Future

They will have made a daughter together — Maggie and them. He will only find this out at the funeral. He will stare at Maggie’s body lying lifeless in the coffin and wonder what they would have made together — Maggie and him.

He will have no idea what has happened in their life over the past eighteen years because by then he will already have decided to cut ties with them, and, by extension, Maggie; because by then they will have said — in one of those contentious us-versus-them, no-gray-areas debates that were the order of the day back then — “Dorian St. Clair has done as much for Black performers as D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation.” It had been an extreme attack at a time when he was feeling particularly vulnerable. They had just married Maggie and he had not been invited to the wedding — not that he would have gone. He had tried to take the higher road and sent them a text which expressed a magnanimity that he certainly did not feel: “Congratulations! Someone always gets the girl.” They had replied during their wedding,

“Maggie was already a woman when we met her.” Who responds to a text during their wedding? he had wondered.

By the time of the funeral, it will have occurred to him that The Birth of a Nation comment had not been a response to his portrayal of Dorian St. Clair, but rather to the fact that the Post-Race International Movement (PRIM) had started not only funding his show (the entertainment industry had always had strange bedfellows) but also calling for the dismantling of positions like theirs at universities and many universities had started heeding the call (academia, too, had always had strange bedfellows). At the time, though, he had been sure that they had said what they did because they had never forgiven him for drawing Maggie away from the bald head, the workman’s boots and the blue overalls and towards the poster with its too easily torn off fringes.

At the funeral, they will be generous enough to allow him to sit with them in front, the previ- ously unknown daughter between them. Growing old will have had a mellowing effect on them, or maybe it will have been the being loved by Maggie for so many years.

He will be aware that, while he only has eyes for Maggie and her shocking head of white hair, most of the people in the funeral parlor only have eyes for him. There would have been a time when the people would have looked at him because he was Dorian St. Clair, but he will not have been Dorian St. Clair for almost ten years now and so they will be looking at him because he is the man who will live forever.

He will not live forever, of course. Barring any accident, the lab coats say, he could make it up to 150 years old. The lab coats suspect that he will eventually begin to show signs of aging, even though it’s unclear what those will be. The lab coats will wonder — no, they will not like that word — they will speculate, hypothesize, theorize about whether the aging process will manifest itself physically or mentally in him, if at all. They will watch — no, that’s another word they will not like — they will monitor, study, observe him morning, noon, and night. They will check his vitals, run tests, make him do various activities and record everything: the genome and epigenome excised from samples of tissue; the levels of antioxidants and oxidants; the efficacy of methods that accelerate and decelerate the aging process; the response of his cells to physical, chemical and biological agents; the creation and presence of possible endogenous threats; the new identities of his rejuvenated cells; the accumulation (or lack) of genetic damage. To maintain this level of care, the lab coats will visit his home in shifts, trying to understand how and why he is one of the first people in the world for whom this course of gene therapy has been successful.

The lab coats will eventually outnumber his fans. No one will have said it — not the network executives, not the showrunner, not his agent, not his fans, not his detractors — but he will know that at some point it had become odd, too uncanny, perhaps even somewhat off-putting to watch a man not age. In an act of desperation, he will dye his hair, but that will only make the situation worse somehow.

At the funeral, he will look at them with their naturally graying hair, their still-smooth but softly sagging skin — under the eyes, around the mouth, under the chin — which will make everything old seem new again. He will watch as a tear travels down these gentrified parts of their face. He never will have thought them beautiful before this moment; he will think them beautiful for the rest of his life.

Something else will catch his eye. The eternal circle of gold, dangling large and shimmering from the previously unknown daughter’s left ear. An inheritance. He will remember having been drawn to that loop, drawn into Maggie. He will also remember the bald head, the workman’s boots and the overalls. He will remember Maggie always running to give them and their political cause a hug. He will remember the searching and will wonder if it had been his all along. He will remember a warmth of which he will not be sure he was ever really a part.

“You think those clinical trials are responsible for what has happened to Maggie?” he will ask them as they both watch the coffin being lowered into the ground.

“I think this is how and where we all end up,” they will say calmly as they let fresh earth fall from their hand and dust the coffin. The previously unknown daughter will do likewise, and he will follow suit. The previously unknown daughter will smile at him and take his dusty hand in hers. Again, he will wonder what he and Maggie could have made together. There is a loss he will feel as a sharp pain that cuts at a very particular angle, forcing him to ask himself questions that he will never have answers to.

“You will join us at the house,” they will say. “A little gathering of those who knew and loved her.” The mixture of provocation and resentment will have gone because old eyes only carry hope in the rightness of rain.

The house will be cozy and lived-in and have an inviting smell, like whatever is cooked there has been passed down from generation to generation — curried goat, jerk chicken, oxtail stew, pepperpot. It is only then, while enveloped by that comforting smell, that he’ll let himself cry. The lab coats will try to enter the home because even in that moment they will be monitoring his vitals and know that something is not quite right with him. They, the one-person protest, will deny the lab coats entry and he will be grateful.

Afterwards, when he has cried his private tears, they will allow him to stay the longest, to be the last guest to leave. They will hand him something as he walks out the door. “Maggie wanted you to have this,” they will say. It will be Maggie’s portrait of him as a young man, but not as he will have remembered it. Its background will be a plain beige, there will be no iconography. His shadowy likeness, however, will be as he remembers it, unchanged.

“She said she painted this in the style of a famous Harlem Renaissance artist,” he will say.

He will know that in the past his not remembering the name of the artist would have led to some kind of confrontation, but now they will only sigh and say, “Aaron Douglas.”

He will be thankful that they have been generous and kind to him all day, and seeing this as an opening to be fully understood, he will say, “Dorian St. Clair was just a character I played on a show on a streaming service.”

“I know, but while you were playing him, who was playing you?” they will say as they give him a hug. He will realize that it is the first time that they have touched in their long knowing of each other. Understanding travels both ways.

The lab coats will already have opened the car door as he walks away from their well-lit veranda. He will hesitate, raise his free hand, the one not carrying the misremembered portrait, and wave. They will wave back. Maggie will have come and gone and left both of them standing, one of them older and wiser, the other hopefully changing.

Before he joins the lab coats in the car, he will look back at them — parent and child — just in time to see the eternal circle of gold catch the light and glimmer.

“Veve,” he will hear them say to their daughter as they lead her back into the house and shut the door behind them.

Certain things are not supposed to work. Things you find at the back of magazines, things you see advertised on television at 3 a.m., things you tear off in small rectangular strips — these things are not supposed to work.

But then again certain things are meant to work and they work beautifully.